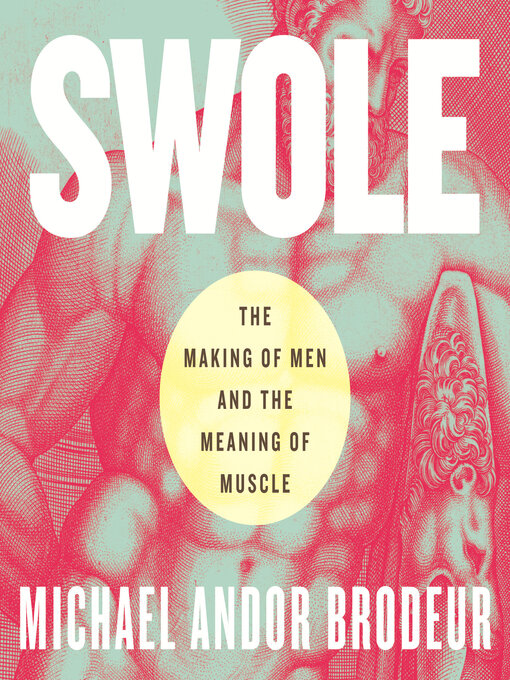

Michael Andor Brodeur is a Gen-X gay writer with a passion for bodybuilding and an insatiable curiosity about masculinity—a concept in which many men are currently struggling to find their place. In our current moment, where “manfluencers” on TikTok tease their audiences with their latest videos, where right-wing men espouse the importance of being “alpha,” as toxic masculinity and the patriarchy are being rightfully criticized, the nature of masculinity has become murkier than ever.

In excavating this complex topic, Brodeur uses the male body as his guide: its role in cultures from the gymnasia of ancient Greece to Walt Whitman’s essays on manly health, from the rise of Muscular Christianity in 19th-century America to the swollen superheroes and Arnold Schwarzeneggers of Brodeur’s childhood. Interweaving history, cultural criticism, memoir, and reportage, laced with an irrepressible wit, Brodeur takes us into the unique culture centered around men’s bodies, probing its limitations and the promise beyond: how men can love themselves while rejecting the aggression, objectification, and misogyny that have for so long accompanied the quest to become swole.

-

Creators

-

Publisher

-

Release date

May 28, 2024 -

Formats

-

OverDrive Listen audiobook

- ISBN: 9780807035061

- File size: 270230 KB

- Duration: 09:22:58

-

-

Languages

- English

-

Reviews

-

Publisher's Weekly

April 1, 2024

Brodeur, a classical music critic for the Washington Post, debuts with a winsome and insightful blend of cultural history and memoir that tracks the idealized beefcake body from ancient Greece to today and chronicles his own queer coming-of-age transformation from “wispy, waify string bean of a boy” to “meathead.” The historical segments shed particular light on contemporary fitness culture’s development, explaining how it first emerged in early 19th-century Germany in deep entanglement with nationalist principles, and was brought to the U.S. by failed 1848 revolutionaries. Throughout, Brodeur maintains a sharp focus on the way Western culture’s perceived mind-body divide has shaped ideas about masculinity (during what he calls American men’s “first identity crisis” in the mid-19th century, the Atlantic Monthly lamented that “a race of shopkeepers, brokers and lawyers could live without bodies”). This ideological undercurrent also surfaces in the autobiographical sections. Of his teenage years, Brodeur writes: “I longed to forget I even had a body. I started thinking of myself as my thoughts.” He builds up to an intriguing hypothesis concerning today’s extremist online culture of men seeking to reclaim a lost masculinity characterized by physical fitness and misogyny. Its catalyst, according to Brodeur, was the internet itself, which, by chipping away at real-life interaction, has set in motion another identity crisis over the separation between mind and body. Punchy, entertaining, and perceptive, this delivers. -

Kirkus

April 15, 2024

A self-described "meathead" writes compellingly about the world of bodybuilding. "I am trying to get Big, and doing it very much on purpose. No, I am not sure why. Yes, you can feel my arm." So writes Brodeur, who, at a glance, might seem an unlikely candidate for bodybuilding: He is, after all, the classical music critic for the Washington Post. But there's more to bodybuilding than meets the eye. It's the locus of a gay subculture, a highly visible means of self-expression, and a way of both adopting and subverting he-man ideals--and besides, "I also really love how my ass looks." Brodeur takes readers on a wide-ranging tour of lifting and the cultural factors that propel "the long physical and psychological road of consciously building one's body." One is the world of childhood, in which many boys played with musclemen dolls and unconsciously absorbed their physical ideals; another was the openness of the bodybuilding culture to those who were once the "klutzes who sucked very conspicuously at team sports and grew up to opt for the weight room over the battlefield or the ball field." Brodeur is consistently funny, but he is also a cleareyed student of the culture with a trove of trivia to fall back on: Who knew that Lou Ferrigno's Incredible Hulk body double was a Black bodybuilder (no matter, since the filmmakers decided "green is green") or that some current bodybuilding ideals can be traced to Dutch Renaissance art? Allowing that there are all sorts of prejudices against it, Brodeur, in the end, delivers a host of good reasons for picking up the weights and putting those muscles to work. A memoir, history, and critical essay in one, sure to captivate anyone who's ever pumped--or dreamed of pumping--iron.COPYRIGHT(2024) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

-

Formats

- OverDrive Listen audiobook

subjects

Languages

- English

Loading

Why is availability limited?

×Availability can change throughout the month based on the library's budget. You can still place a hold on the title, and your hold will be automatically filled as soon as the title is available again.

The Kindle Book format for this title is not supported on:

×Read-along ebook

×The OverDrive Read format of this ebook has professional narration that plays while you read in your browser. Learn more here.